EXCERPT FROM; TWO PLANKS AND A PASSION, BY ROLAND HUNTFORD | PHOTOS; SKIMUSEET

While equipment advanced, ski touring, inspired by Nansen, did so too. His crossing of Greenland triggered its polularization. This began in Nordmarka, the as yet unspoiled skiing hinterland of Christiania (former name of Oslo). The size of an English county Nordmarka, with its high, protected, rolling terrain, running down to the city, meant touring on the doorstep. It had long attracted pioneers; it was now interleaved with an urban population in a way found nowhere else outside Scandinavia. Here was the cradle of modern Nordic skiing, with its blend of man-made infrastructure and contact with the natural world.

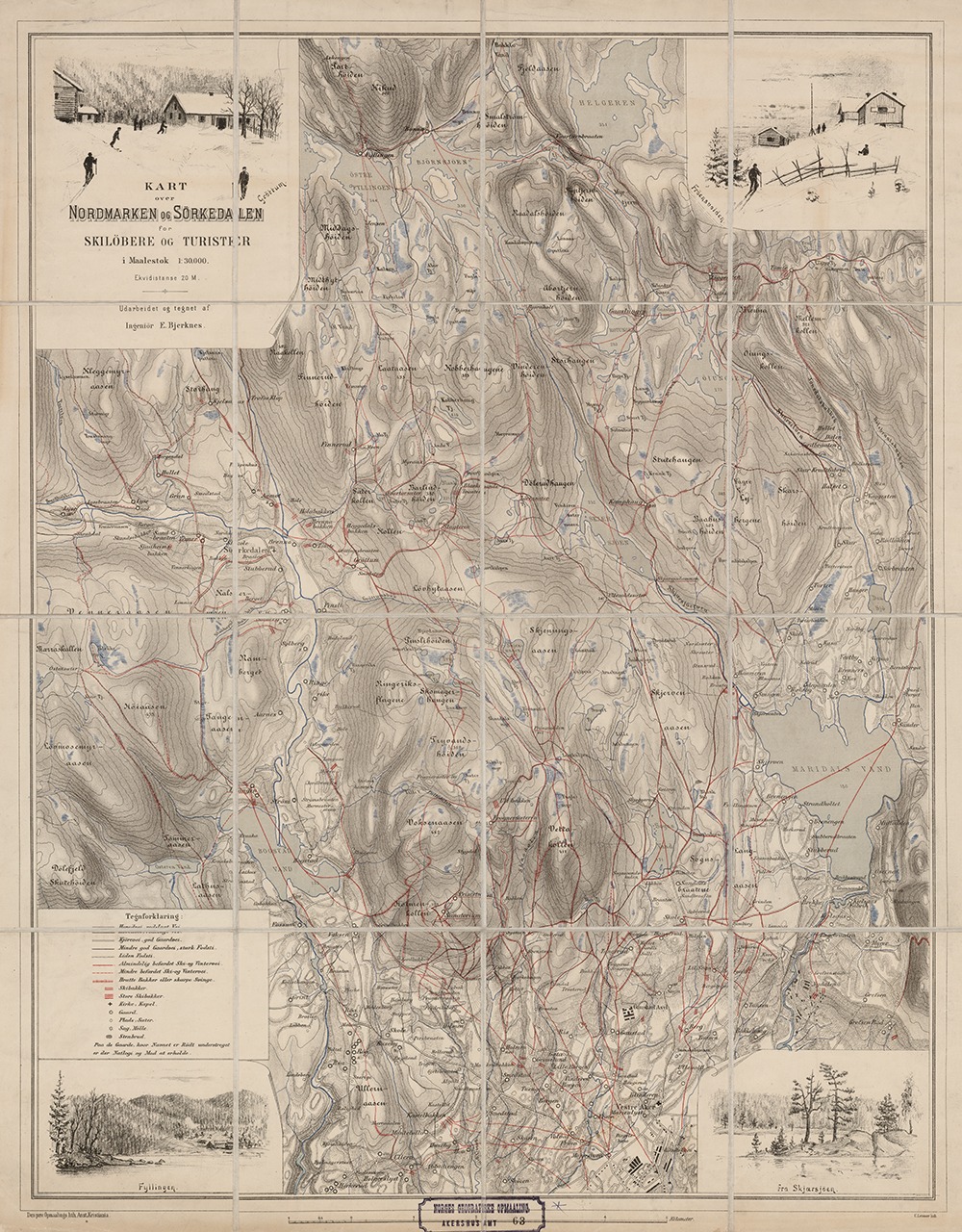

It owed much to the Ernst Bjerknes who had so notably recorded an early ski-jumper’s lot. In 1887, at the age of 22 he qualified as an engineer and found himself unemployed. ‘To have something with which to occupy myself’, as he put it, ‘I decided to produce a map of Nordmarka, on which I would mark all known ski tracks’.

Nordmarka was many things. It was part mountain farmland, part untamed heath, part undulating woodland dotted with lakes. Within living memory wolves had padded between the trees. It was no conifer jungle but rather a working forest. With undergrowth cleared and managed space, it was a natural skiing nursery. Ski tracks sometimes followed logging roads, paths and cattle runs. Nothing, however, was signposted; everything was stored in memory and tradition. Skiing had grown out of the landscape. In his own words, Bjerknes ‘went on a journey of exploration in Nordmarka. I carried on all summer and long into the autumn. (I went) through undergrowth and bogs, after all it was winter tracks that I was looking for. I asked about ski tracks (everywhere), and gradually I drew the red lines on the map’.

It came on the market in the wither of 1889 as Nansen fever broke out – and luckily so. Bjerknes had to publish the map himself, and sold it on subscription. The customers flocked round. Without Nansen the map might not have appeared.

Amundsen, like others, had played Nansen crossing Greenland on the tracks near his home but at some point crossed the line between make-believe and reality. Such men are dangerous because they have the gift of acting out their dreams. Amundsen had decided to become a polar explorer himself. To him, the ski was obviously the key to success. He had to begin, therefore by training as a mountain skier, because that was like a nursery of polar exploration. Urdahl seemed the answer. He had written about his own mountain tours in the Press.

Urdahl received many requests to follow him on his ski tours. All were politely declined, until Amundsen appeared. He had connections. They were related by marriage. Urdahl agreed to take him on his next excursion so that, as he said, Amundsen ‘would be initiated into the mysteries of the high mountains in midwinter’. …crossing Hardangervidda once more on skis. This was the training enterprise that Amundsen was to share.

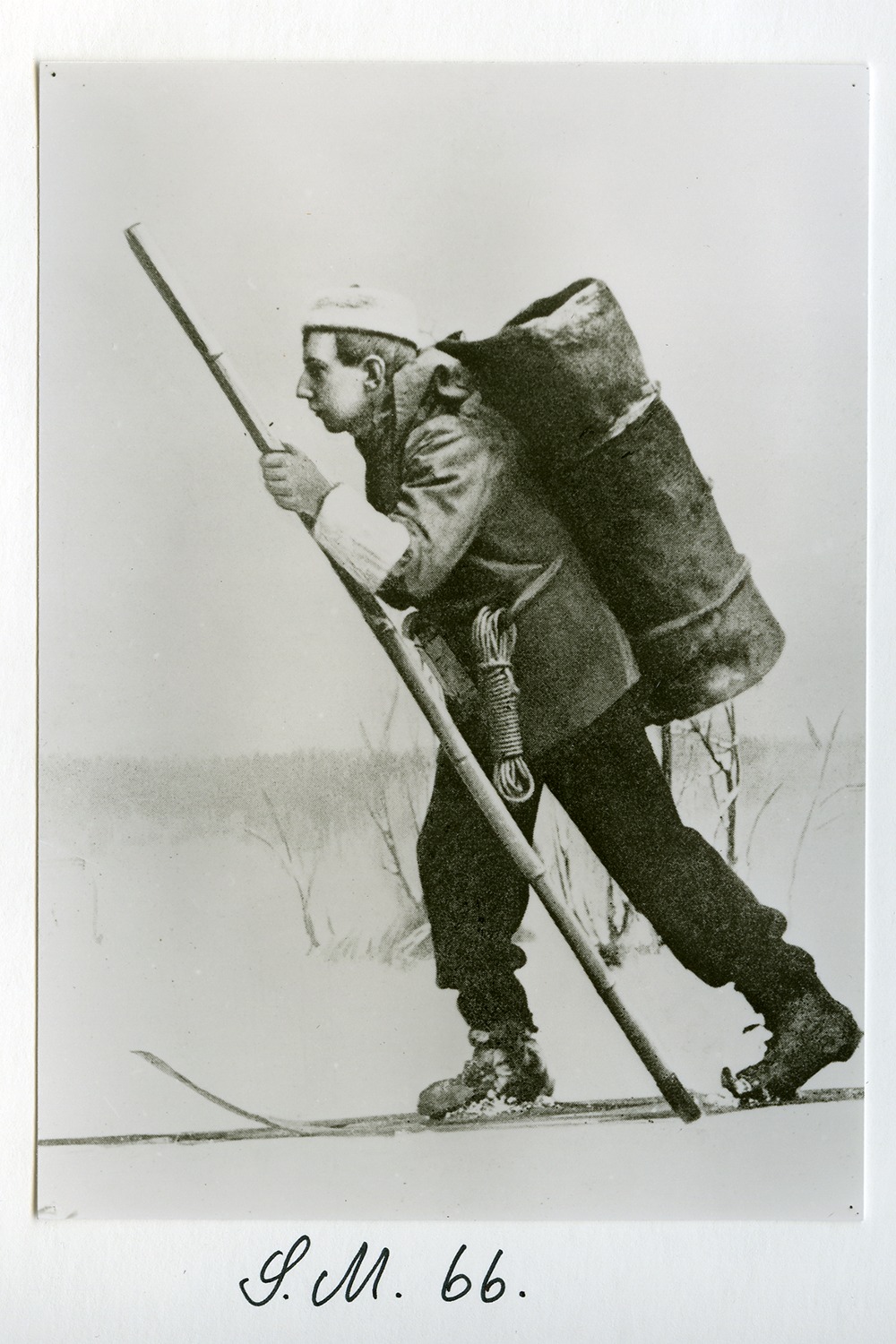

They left Christiania by train on Christmas Day 1893, reaching the railhead at Krøderen, at the entrance to the valley of Hallingdal, the road to Hardangervidda, in the afternoon. They immediately began skiing, weighed down by the usual bulky reindeer sleeping bag topped with other impedimenta. Among the special clothes to fight the wind and cold, said Urdahl, ‘we particularly put our trust in an Anorak (Greenland jacket) of waterproof material’. Applied to skiing, this is one of the earliest examples of the word in print.

…demonic winter raged over the wild terrain, with the usual blizzards, unpredictable skiing, forced bivouacs and wildly fluctuating temperature from thirty degrees of frost to arbitrary thaws. In fact, the going was so poor and the delays so great that Urdahl finally had to turn back and go to Ålesund by another route so that he could start his new job in time. Holst and Amundsen were left to carry on alone but they could not prevail against the elements. They too had to turn round and head for home without crossing Hardangervidda.

It was two years later. Amundsen’s companion was now his elder brother Leon. Amundsen had hoped to accomplish the now legendary winter crossing of Hardangervidda, which had defeated him in 1894. He and Leon left Christiania on 3 January 1896. Urdahl published his letter unedited and uncut. It was spread over six generous instalments. It was one more addition to the now established genre of the ski tour as a newspaper feature.

Hardangervidda was a fitting simulacrum of Arctic and Antarctic. At an altitude of 600m, it was naked and exposed, its only vegetation being scrub and lichen and subarctic plants. Visited in summer by both hunters and tourists, in winter the plateau was still uninhabited. Without natural protection it was prey to the weather driving in from the North Atlantic. Wind-gouged hummocks told the tale of blizzards sweeping over the treeless expanses of unrelieved snow with fickleness worse than the polar regions, compounded by the eerie sense of human habitation since prehistoric times, when the first men visited the heights from the coastal strips where they were clinging to existence.

The plateau lay calm and quietly. It was resting after the effort of yesterday, and gathered new strength for another attack.

How fantastically beautiful is… Nature, even if it only consists of snow and ice! The sun rose up in purple-red tints, and coloured the tops of the endless hillocks gold. It was a wild landscape that lay before us, but you would have to search far and wide for one that was more beautiful.

This is typical specimen of the deistic nature-worship that informed the early ski tourers, and survives among their Scandinavian descendants still. It was written in the glow of retrospection. Whether such philosophy actually helped at the time was another matter altogether. Amundsen and his brother found themselves aimlessly wandering about the plateau, unable to reconcile compass with map, sleeping out in the snow, battered by cold and storms.

Amundsen and his brother never finished the crossing. They had to turn back and go home. In an editorial footnote, Urdahl praised Amundsen’s ‘unusual unpretentious style’:

They were lost in the storm-swept mountains for 8 ½ days, and for 3 ½ days they were completely without food, whilst at

the same time they had to cope with great exertion. To those who read the report, it seems as if the tour has been a trifle for Herr Amundsen. He does not even mention the ugly frostbite which he and his brother sustained… and which threatened amputation of fingers for weeks afterwards. But Amundsen is a great figure, with a little of the old Norwegian Viking…. next winter, if we are not mistaken, he proposes to make another attempt to cross Hardangervidda.

In fact, Amundsen never did so. Hardangervidda remained for him the demon that he could not overcome but only circumvent.